Health And Safety In Quarrying

This paper is the fourth in a series of five based on a CD-ROM of lecture and training material covering the fundamentals of health and safety management. The CD-ROM was prepared by the Camborne School of Mines on behalf of EPIC (NTO) Ltd and the Health and Safety Executive (HSE), and distributed to all providers of quarry-related courses in higher education. This paper focuses on two separate aspects of safety management: first, accident investigation, and secondly, managing the safety and health of contractors.

ACCIDENT INVESTIGATION

Accident investigation is an important part of any safety management system. Without a detailed and thorough investigation, management has no true knowledge of the reasons why accidents occur and how to prevent their reoccurrence. The primary purpose of accident investigations is to improve health and safety performance by:

- exploring the reasons for the event and identifying both the immediate and underlying causes

- identifying remedies to improve the health and safety management system by improving risk control, preventing a reoccurrence and reducing financial losses.

What to investigate

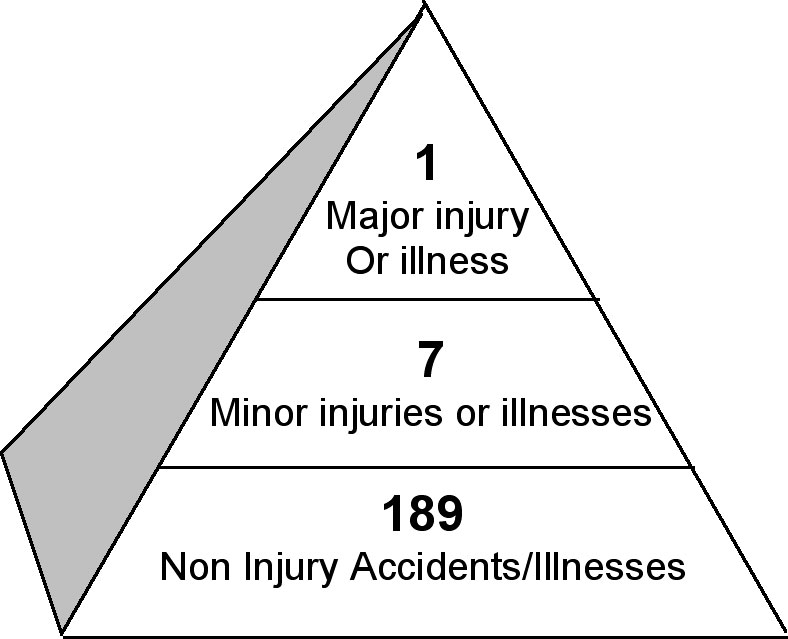

All accidents, whether major or minor, are caused. Serious accidents have the same root causes as minor accidents and so do incidents with a potential for serious loss. It is these root causes that bring about the accident; the severity is often a matter of chance. Accident studies have shown that there is a consistently greater number of less-serious accidents than serious accidents and, in the same way, a greater number of incidents than accidents. The results of such studies have been represented as triangles. Many accident ratio studies have been undertaken and the one shown in figure 1 is based on studies carried out by the Health and Safety Executive1.

In all cases the ‘non-injury’ incidents had the potential to become events with more serious consequences. Such ratios clearly demonstrate that safety effort should be aimed at all accidents, including unsafe practices at the bottom of the pyramid, rather then just targeting the serious accidents at the top. In theory, such practices will cause reductions from the base of the pyramid upwards. Peterson2, in defining the principles of safety management, says that ‘an unsafe act, an unsafe condition, an accident are symptoms of something wrong within the management’s system’. All events represent a degree of failure in control and are potential learning experiences. It follows, therefore, that all accidents should be investigated to some extent. This extent should be determined by the loss potential rather than just the immediate effect.

Stages in an accident/incident investigation

The stages in an accident/incident investigation are shown in figure 2.

Preparation

Dealing with immediate risks

When accidents and incidents occur immediate action may be necessary to:

- make the situation safe and prevent further injury

- help, treat and, if necessary,rescue injured persons.

An effective response can only be made if it has been planned for in advance. Although the timing of accidents and incidents is unpredictable, it is usually possible to foresee the majority of events and prepare emergency plans to deal with them when they occur. This is a particular requirement of the Management of Health & Safety at Work Regulations, 1999, as well as Regulation 15 of the Quarries Regulations, 1999.

Selecting the level of investigation

As stated earlier, all accidents and incidents need investigating to some extent. The greatest effort should be put into:

- those involving severe injuries, ill-health or loss

- those which could have caused much greater harm or damage.

These types of accidents and incidents demand more careful investigation and management time. The effort in investigating these accidents needs to be proportionate to the actual or potential risk. This can usually be achieved by:

- looking more closely at the underlying causes of significant events

- assigning the responsibility for the investigation of more significant events to more senior managers.

Getting the facts

The purpose of investigations is to establish:

- the way things were and how they came to be

- what happened, ie the sequence of events that led to the outcome

- why things happened as they did, analysing both the immediate and underlying causes

- what needs to be done to avoid a repetition and how this can be achieved.

A great deal of information is available after every accident. Establishing what is relevant and what is not can be time consuming, and some facts will be of greater importance than others. The investigator’s problem is to determine and concentrate on the most important. A few sources should give the investigator all he needs to know. These are shown in figure 3.

Interviews

Interviewing the person(s) involved and witnesses to the accident is of prime importance. Ideally it should take place in familiar surroundings so as not to make the person feel uncomfortable.

Ferry3 states that it is impossible to provide interviewing technique guidelines that can be used in all situations, but there are some broad guidelines that can be used with care:

- The style of interviewing is important. It should be restated time after time that the purpose of the investigation is not to apportion blame but to prevent reoccurrence.

- A more co-operative attitude will be achieved if management can promote this positive culture by demonstrating the need to determine the cause rather then to blame or punish.

- The persons involved should give an account of what happened in their terms rather than the investigator’s.

- Interviews should be separate to stop people from influencing each other.

- Questions, when asked, should not be intimidating as the investigator will be seen as aggressive and reflecting a blame culture.

Observation

The accident site should be inspected as soon as possible after the accident. After looking at the site as a whole, particular attention should be given to individual factors such as:

- positions of people

- personal protective equipment (PPE)

- tools and equipment and plant or substances in use

- orderliness/tidiness.

Documents

Documentation to be looked at includes:

- written instructions, procedures and risk assessments which should have been in operation and followed.

The validity of these documents may need to be checked by interview. The main points to look for are:

- is it adequate/satisfactory?

- was it followed on this occasion?

- were people trained/competent to follow it?

- records of inspections, tests, examinations and surveys undertaken before the event. These provide information on how and why the circumstances leading to the event arose. The knowledge, skill and competence of those carrying out the tasks covered in the records may have to be assessed.

Determine causes

It is important that all the information and facts which surround the accident are collected before thinking about possible causes. As soon as the investigator starts thinking about causes, the ‘fact-finding’ stops, the cause has been found and anything else is incidental. This is known as the ‘Stop Rule’4.

Immediate causes are obvious and easy to find. They are brought about by unsafe acts and conditions and are the ‘active failures’. Unsafe acts show poor safety attitudes and indicate a lack of proper training. If the investigator determines that an unsafe act was a contributing factor, the reason for this must be found. In the same way, if an unsafe condition was found to be an obvious cause its source must be determined and corrected.

These unsafe acts and conditions are brought about by the so-called ‘root causes’. These are the ‘latent failures’ and are brought about by failures in organization and the management’s safety system. These could include1:

- the adequacy of health and safety policy

- how work is controlled, co-ordinated and supervised

- how the co-operation and involvement of employees is achieved

- the adequacy of the communication of health and safety information

- how competency is achieved and tested

- the adequacy of planning, risk assessment and control measures

- the adequacy of planning and monitoring activity

- the adequacy of review and audit arrangements.

Active and latent failures were outlined in the first paper in this series.

Determine what changes are needed

The purpose of the investigation is to prevent a reoccurrence. To do this some practical measures must be recommended and carried out to demonstrate that management are committed to this. The investigation should determine what control measures were absent, inadequate or not implemented, and some form of remedial action should be implemented to correct this. Generally, remedial actions should follow the hierarchy of risk control:

- Eliminate risks by substituting the dangerous by the inherently less dangerous.

- Combat risks at source by engineering controls and giving collective protective measures priority.

- Minimize risk by designing suitable systems of working.

- Use PPE as a last resort.

Recording and analysing the results

The findings of every investigation need to be recorded in a similar and systematic manner. This is so that the report can be read by the people responsible for reviewing and implementing the necessary changes and to provide a basis for communication. The report also provides a historical record of the accident that will be useful in the future. A description of the accident, analysis of the causes and recommended preventative protective measures should be listed. This report or form should be completed as soon after the accident as possible.

Information on the accident and remedial actions should be passed to all supervisors who should ensure that employees under them, who may or may not encounter similar accidents, are knowledgeable about the events. The appropriate preventative measures may also have to be implemented by such supervisors. Information can also be transferred in a number of other ways which are effective, such as through bulletin boards, meetings, inspections and, in particular, through safety audits.

Investigation reports and accident statistics should be analysed from time to time to identify common causes, features and trends that may not be apparent from looking at events in isolation.

Reviewing the process

Reviewing the accident/incident investigation process should consider:

- the results of investigations and analysis

- the operation of the investigation system (in terms of quality and effectiveness).

Line managers should follow through and action the findings of investigations and analysis. Follow-up systems should be established where necessary to keep progress under control.

The investigation system should be examined from time to time to check that it consistently delivers information in accordance with the stated objectives and standards. This usually requires:

- checking samples of investigation forms to verify the standard of investigation and the judgements made about causation and prioritization of remedial actions

- checking the numbers of incidents, near misses, injury and ill-health events

- checking that all events are being reported.

MANAGING THE HEALTH AND SAFETY OF CONTRACTORS

The term ‘contractor’ refers to any individual or organization who enters into an agreement with a company to carry out services. There is a continual trend towards increasing the use of contractors in the quarrying industry and the activities carried out by contractors are no longer restricted to those of the ‘specialist’; they now include routine quarrying activities such as vehicle driving, drilling, blasting etc.

Contracts in the quarrying industry can be classified as shown in table 1.

With respect to contractors, a company’s time and resources are frequently allocated in proportion to the size of the contract. Therefore, major and medium-size contracts use formal contractual documentation and processes are more detailed and thorough. Minor contracts and casual contracts are generally less well controlled with perceived bureaucratic procedures and processes being avoided. As a result, health and safety issues may require more vigilance with relatively minor contracts.

The majority of the following measures are either explicit or implicit requirements of current legislation, including the Management of Health and Safety at Work Regulations, 1999. They are essential for all contractor operations regardless of the size of the contract.

The quarry/contractor relationship

While the use of contractors provides the industry with advantages such as flexibility, fixed costs etc, the health and safety implications for a company using contractors are just as onerous as those applying to its own employees. Responsibilities when employing the contractor are set out below.

All companies have a duty under the Health and Safety at Work Act, 1974, to take all reasonably practicable steps to ensure the health and safety of:

- their employees

- other people at work on the site, such as contractors

- members of the public who may be affected by the work.

As a company, the contractor also has a duty to ensure the safety, health and welfare of its employees and others who may be affected, wherever they may work. They must provide a safe place of work and a safe system of work on clients’ premises, just as they are obliged to on their own premises.

Under the Management of Health & Safety at Work Regulations, 1999, all employers are required to undertake an assessment of the risks which effect employees and anyone else who may be affected by the work, including contractors. Other duties include the provision of training, co-operating with others on site (including contractors) on health and safety matters, and providing health and safety information.

Managing the health and safety of contractors

Five steps to managing the health and safety of contractors are given in figure 4.

Planning

The first step is to plan what the contractor’s job involves and how it can be done safely. After defining the scope of work, a risk assessment should be carried out to identify any significant potential hazards to safety and health. Following this the company should develop a bid list through a formal or informal pre-qualification process which includes the scope of work, the risk assessment and other tendering information. Contractors also have a responsibility to carry out a risk assessment and should do so before work commences at the tender stage.

In order to be satisfied as to the competency of the contractor in the management of health and safety, it is common for companies to send out or use a pre-qualification checklist at the tendering stage. A list of the minimum health and safety requirements for small contractors that could be used as the basis of such a checklist is shown in table 2.

Selecting a contractor

Once tenders have been received they should be evaluated to establish whether the contractor has:

- an appropriate health and safety management system (such as policies, procedures and practices) that are in keeping with the task in question and the standards set by the employing company and legislation

- the resources necessary and available to implement that management system on site

- carried out a risk assessment and documented a safe system of work

- a good record of occupational health and safety performance in work of a similar nature.

Some companies may have a list of ‘approved contractors’ who meet all the requirements listed above and are reassessed on an annual basis, rather than before each particular job.

Working on site

Once a contractor commences work on site it is important that they are aware of the site safety rules that apply to them and any particular hazards that they face. It is good practice to:

- control the coming and going of contractors in and out of the premises

- provide induction on the site conditions, facilities, safety rules and practices required

- name a site contact (someone to get in touch with on a routine basis or if the job changes and there is uncertainty about what to do). This person should besomebody nominated who is in a managerial position with sufficient authority and competence (such as the production, operation or safety manager on site). This person should go through the job with the contractor to ensure that all necessary controls are in place (such as permits to works, PPE, procedures etc)

- establish a timetable for formal and regular review of the contractor’s safety management system through inspections, audits and safety meetings.

Keeping a check

Having established a timetable for over-inspections and audits of the contractor’s health and safety management system, it is important that this is undertaken in order to ascertain how the job is going, in particular:

- is it going as planned?

- are the contractor’s health and safety systems actually in place and are they being followed?

- are they working safely?

- have there been any incidents?

- are any other special arrangements necessary?

Reviewing the work

Once the job has been completed it is necessary to review the job. Reviewing is about evaluating the quality of the work against both the job and the contractor’s performance. One reason for this is to learn what can be done differently next time in order to:

- review the outcomes and achievements of the contractor

- verify the adequacy of procedures in place

- amend or add to the procedures if necessary

- record and rate the overall performance of the contractor against established criteria

- provide feedback to the contractor.

References

- HSE (1997a), ‘Successful Health & Safety Management’, HS(G)65, HSE Books.

- PETERSON, D.: ‘Techniques of Safety Management’, 2nd Edition, McGraw Hill, New York, 1978.

- FERRY, T.: ‘Modern Accident Investigation and Analysis’, John Wiley & Sons, Canada, 1988.

- STALEY, B.G. and P.J. FOSTER: ‘Investigating accidents and incidents effectively’, Mining Technology, 1996, vol. 78, no. 395, pp 67–70.

- HSE (1997b), ‘Managing Contractors – A Guide for Employers’, HSE Books.

- Chamber of Minerals and Energy of Western Australia: ‘A guide to contractor occupational health and safety management for Western Australian mines’, Perth: Chamber of Minerals and Energy, 1998.