The Dawn Of The Ready-Mixed Concrete Industry

A brief commercial history of the first 50 years from 1913 to 1963

By Michael J. Arthur

When the author entered the ready-mixed concrete business of Trent Gravels Ltd of Attenborough, Nottingham, in 1960, the ready-mixed concrete industry in the UK was still in its infancy. At that time there were people around who had been in ‘ready-mix’ from the start and some of what follows is based on their published comments, the remainder on their private recollections and the author’s own experience from the early 1960s. This article formed the basis of a presentation to the Midlands branch of The Institute of Quarrying in 2003.

It is difficult to pin down the exact starting point of ready-mixed concrete production. A widely quoted date is 1913 but other sources suggest it could have been even earlier, depending upon how the term is interpreted.

In 1913, when the first load of ready-mixed concrete is said to have been delivered by an American in Baltimore, concrete was commonly mixed by hand, but in 1916 Stephan Stepanian of Columbus, Ohio, filed a patent for a truckmixer. This was rejected, however, and the ‘transit mixer’ took another 10 years to materialize and to deliver the first load of truck-mixed concrete in 1926. In the meantime (believed to be in 1922 or 1923) a building materials supplier from Danville, Virginia, bought a concrete mixing plant for his own use and soon recognized the opportunities for supplying other contractors. By 1925 there were some 25 plants in production, and by 1929 over 100 concrete-mixing plants were in existence throughout the US.

This is the standard story of the development of ready-mixed concrete, which credits the Americans with the invention of what has become the main source of the material for construction work. In his paper entitled ‘The growth of the ready-mixed concrete industry in Great Britain’, however, Peter Jackson tells of a Mr Deacon, Liverpool’s Borough and Water Engineer, who in 1872 carried out tests to satisfy himself that concrete compacted 20–30min after mixing gave better results than when used immediately. Over the next five years he went on to lay some 100,000yd3 of concrete ‘after being mixed in and carried from the nearest available yard’.

Jackson’s paper also records that ‘ready-mixed concrete’ was used in the construction of the Admiralty Harbour at Dover in 1898 and in one section of the work there were two 1yd3 mixers, each producing 100yd3 of concrete a day.

So Peter Jackson’s article, published in the March 1957 edition of the magazine Cement, Lime and Gravel, puts a new complexion on the history of ready-mixed concrete, although he does admit that the term is now only applied to the situation where the producer ‘sells’ concrete to a user, and this is what is supposed to have happened first in Baltimore in 1913.

The background to developments in Britain

Although the industry ‘took off’ in the US during the 1920s, post-World War I Britain experienced no such development and at the end of the 1920s there were no central mixing plants in the UK. In the March 1930 edition of Cement, Lime and Gravel, however, the editor made the following comment: ‘Our conservative nation is famous for its care in accepting new ideas and this has delayed the introduction of ready-mixed concrete here.’ But he added: ‘It’s got to come’, and indeed it did. Simon McPherson’s comment accompanied an article entitled ‘Ready-mixed concrete and central mixing plants’ by J.L. Wellings of Millars Machinery Co. Ltd, which was claimed to be the first comprehensive article on the subject published in the UK.

Wellings described the situation in the US industry in the 1920s and distinguished between concrete from ‘central mixing plants’ and ‘truck- or transit-mixed concrete’. The former he classified as ‘stationary’ and ‘semi-portable’ for the production of wet-mixed materials, and both of them for mixing dry materials.

The plants illustrated varied in appearance, but each contained the essential elements of aggregate and cement storage. Bulk cement handling through the use of an ‘air-conveying system’ was considered more satisfactory than the use of bagged cement.

The vehicles used for delivering low-slump wet-mixed concrete were either standard tippers or those with specially built V-shaped bodies, while tipping ‘agitators’ were employed for conveying higher-slump mixes. Non-tipping, horizontal-drum truckmixers, which incorporated a scroll of blades, were rotated in one direction to mix the dry batch, and in the other to discharge the mixed concrete. It is interesting to note that as late as 1945, D.C. Hay of Kuert Concrete Inc. was reporting that his company used nothing but non-agitating tippers to deliver 55,000yd3 of ready-mixed concrete a year, over distances of up to 28 miles from the plant.

J.L. Wellings quoted the capital outlay for a central mixing plant installation and trucks in 1930 as being £20,000 for a modest unit and up to £90,000 for a large one incorporating a 3yd3 mixer. The truckmixer fleet would account for some 60% of this outlay, with a 2yd3 machine costing some £2,000. He commented that one company had 86 trucks in use, another 64, and observed that several large plants had this number handling their output!

Britain in the 1930s

The person credited with being first off the mark in the UK was Kjeld Ammentorp, a Dane, who had witnessed the introduction of ready-mixed concrete in Copenhagen in the mid-1920s. He formed a company called Ready Mixed Concrete Ltd in July 1930 and erected the UK’s first plant on land owned by Hall & Co. at Bedfont, near Staines in Middlesex. Peter Jackson refers to him as the ‘father’ of the British ready-mixed concrete industry, and indeed he was. Having selected such an appropriate name for his business, he was to become a guiding light for several of the people running the companies that were to follow.

The Bedfont plant included a 2yd3 mixer and was fed from four 100yd3 aggregate bins. Cement was initially handled in bags, as bulk cement handling systems ‰ were not readily available in Britain at the time. Gravel and sand were handled by a bucket elevator and the plant had an output of up to 40yd3/h, which was discharged into six truck-mounted agitators, each capable of transporting 12?3yd3 of concrete. His vehicle fleet consisted of Chevrolets and subsequently included Studebakers.

Ammentorp was said to have started with a capital of £6,000 and through the production of a modest 8,636yd3 in 1931 he generated a turnover of £10,000, but suffered a net trading loss of £399. Demand gradually increased, however, particularly as Middlesex County Council saw the benefit of ready-mixed concrete in its road-improvement schemes.

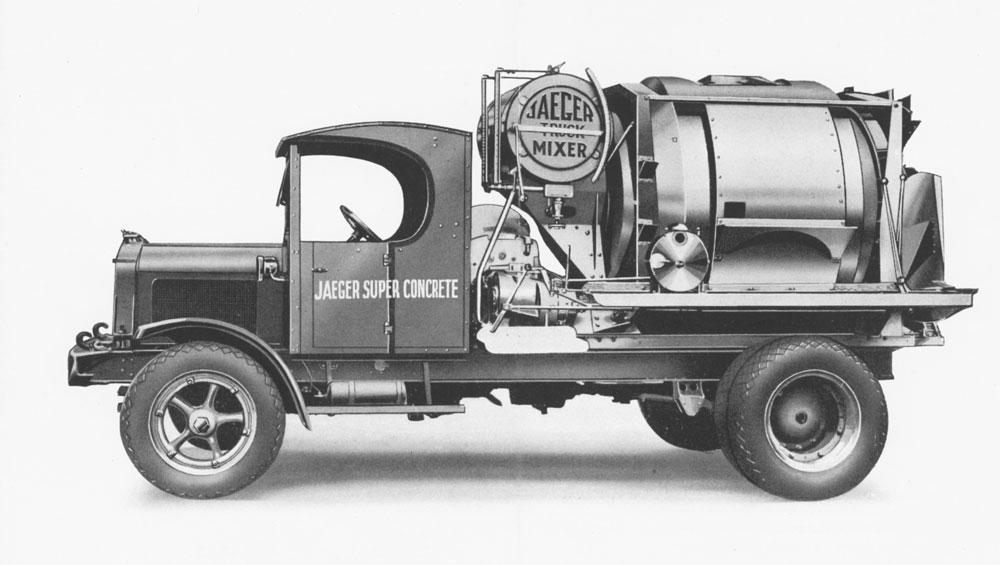

Following the start-up at Bedfont, the next company to appear on the scene were Scientific Controlled Concrete Co. Ltd, who went into business at nearby Staines in 1934. The company used the American-designed Jaeger truckmixers, which were supplied by Ransomes & Rapier Ltd of Ipswich, but Scientific soon went out of business, with some of their plant subsequently being acquired by Truck Mixed Concrete (Southampton).

Another company using agitators and American 5yd3 transit-mixers in the early 1930s were British Steel Piling Co. This company and Mowlem, who owned two truckmixers, collected their own purchases of concrete. Next were Jaeger System Concrete Ltd, who established a base in Glasgow and subsequently operated under the name of Trumix Concrete, later becoming part of the Tilcon organization.

In 1936 Express Supply Concrete Ltd were founded as a subsidiary company of Balfour Beatty Ltd. They operated two plants, the first at Paddington, and the second at Alperton, served by a total of 30 Jaeger truckmixers, but of 2yd3 capacity.

The only other company to set up in business as a ready-mixed concrete supplier in the 1930s were Trent Gravels Ltd of Attenborough, near Nottingham. As a company, they had begun by extracting gravel and sand from the deposits in the Trent Valley 75 years ago in 1929 and by 1937 were beginning to make enquiries about the Jaeger system of ready-mixed concrete production to supply into the Nottingham– Derby–Leicester market area.

Their Jaeger dry-batching plant came into operation in 1939 and in many respects was similar to Express Supply Concrete’s installations, using bulk cement and Jaeger-designed 2yd3 horizontal-drum truckmixers, driven by a separate on-board engine. The plant and the truckmixers at Attenborough were supplied by Ransomes & Rapier Ltd.

Thus, prior to the onset of World War II, there were only five known operators of ready-mixed concrete plants in Britain. Of these only Ammentorp’s Ready Mixed Concrete Ltd were using a central mixing plant with agitators at their Bedfont depot.

Elsewhere, such as in Germany, ready-mixed concrete was also starting to become established on the construction scene. The year 1939, however, was a momentous one in construction terms on the other side of the world. It was in that year that Sam Stirling, an Australian entrepreneur, established a plant in the heart of Sydney and succeeded in registering his company as Ready Mixed Concrete Ltd throughout Australia. His company logo, the word ‘Readymix’, said to be in his own handwriting, was to become established not only in Australia, but, in time, also throughout much of the rest of the world.

Trent Gravels Ltd

Trent Gravels entered discussions with Jaeger Truck Mixers (England) Ltd, sole licensees for Jaeger truckmixers manufactured by Ransomes & Rapier, in 1937. The company also took soundings from Express Supply Concrete in 1938 to arrive at an estimated outlay of £5,500 for the plant and £6,500 for six ERF lorries with mixers and a garage. On an expected annual output of 26,000yd3, projected operating costs for the plant were 1s 6d per cubic yard and for the fleet, 4s 2d. With materials averaging 16s 1?2d, and 3d thrown in for contingencies, production costs totalled 22s per cubic yard. Expected profit per cubic yard was 2s 6d.

The batching plant was supplied with aggregates by belt conveyor from the gravel plant, while bulk cement deliveries were handled by a Fuller Kinyon pump (not unlike a vacuum cleaner and an updated version of the equipment installed by Express), which elevated the cement from the ground-level storage to bins above the weighing floor of the plant.

Again, like Express, Trent Gravels established a brick-built laboratory to house cement-testing equipment, a sand-moisture tester, aggregate sieves, concrete cube-making equipment and a hand-operated Denison cube compression-testing machine. Initial advice on mix design, testing and quality control was under the supervision of R.H. Harry Stanger.

The rapid onset of the war brought added complications to the new business, not least being the unforeseen demand for concrete for bunkers, shelters, runways and holding areas for military hardware. The Attenborough site was within a mile of the MoD’s Chilwell Ordnance Depot and, under wartime conditions, the ready-mixed concrete operation virtually came under the control of the local commanding officer of the Royal Engineers. The small team of men associated with Trent Gravels’ concrete operations were immediately placed on the list of reserved occupations and were deemed to be essential to the war effort at home.

The end of the 1940s began to see a slow recovery after the war, but it was the 1950s that brought a rapid increase in trade for concrete from Attenborough for new council-owned housing, road improvements and, in the middle of the decade, emergency sea-defence work when Trent Gravels’ truckmixers were supplying concrete to the east coast, some 50 miles away.

Demand continued to increase, so much so that a new central mixing plant was established by the company at Mansfield and shortly afterwards in 1958 the Ransomes & Rapier lever-controlled, dry-batch plant at Attenborough was decommissioned when a Blaw-Knox plant, similar to the one at Mansfield but housing two 3yd3 Winget drum mixers, came on stream there too.

This new plant, which supplied a fleet of 22 Attenborough-based horizontal-drum truckmixers (a belt-and-braces approach which contrasted with the use of agitators at Mansfield), was supplied with bulk cement delivered in tippers, which discharged into a receiving hopper. The hopper was emptied by a screw conveyor feeding a bucket elevator, which discharged into a two-compartment silo. From here cement was drawn on demand through an air-slide into a blowing chamber to be conveyed pneumatically to the storage silos at the top of the plant. Pressurized tanker vehicles also delivered cement from the early 1960s onwards. Aggregates were again supplied direct from the aggregate plant by belt conveyor and the batching operation was conducted through an electro-pneumatic push-button system and weigh dials, the operator referring to batching cards giving the weights of materials required for particular volumes of mixed concrete.

Greater throughputs were achieved through this plant, especially with the introduction of larger-capacity, high-discharge truckmixers (at first 4yd3 capacity and then 6yd3). The 1960s were proving to be a boom time for construction work, which in the area included the M1 motorway, an expansion of the University of Nottingham, eventually to include the University Hospital, as well as the development of many private housing estates and inner-city, multi-storey rehousing schemes. One notable contract for Attenborough material was Nottingham’s new Playhouse Theatre, which exhibits a fine array of concrete both inside and out, and, in recent years, was given an award as a commendable example of 1960s’ architecture.

Post-World War II developments

In the 1950s plants started to appear in and around the major cities of Birmingham, Leeds, Leicester, Liverpool, Manchester and Newcastle, in addition to the greater London area. There were two schools of thought — one favouring a large mixing plant with delivery vehicles on an average haul to site of around 7 miles, or, alternatively, a series of small dry-batch plants using a pool of truckmixers.

By 1963, when the international ready-mixed concrete industry reached it’s notional half century and Trent Gravels Ltd were about to celebrate 25 years in the trade, there were many suppliers of ready-mixed concrete in existence. Already by far the largest of these were Australian company Ready Mixed Concrete Ltd (subsequently to become simply RMC), who had entered Britain in 1951 when Sam Stirling sent his envoy,

Bryan Kelman, to spy out the prospects.

In 1952 Kelman arranged a deal worth £92,500 for the purchase of Ammentorp’s operation, which had commissioned a new £28,000 plant two years earlier and by that time was capable of producing some 50,000yd3 a year. From that year onwards Ready Mixed Concrete Ltd grew rapidly through acquisitions and new developments by the go-ahead team headed by Kelman, which included fellow Australian Norman Davis and British civil engineer John Camden, who was to succeed Kelman on the latter’s return to Australia in 1965 to head up CSR. Trent Gravels themselves became part of the RMC group before the decade was out and their concrete operations were taken into the group’s Sheffield-based regional company.

Other major players by 1963 included Hall & Ham River, Trumix, Mixconcrete and Premix, all of whom were later absorbed into larger concerns: Halls to RMC; Trumix to Tilcon and thence to Anglo-American’s Tarmac subsidiary; Mixconcrete to Pioneer and then to Hanson; and Premix (Amey) to ARC and thereby to Hanson. There were of course many more, with ‘catchy’ names, who are now believed to be lost in the mists of time: Automix, Exactamix, Finamix, Mass-ter Mix, Mobilmix, Rotamix, Tufmix and Welmix — to name but a few!

With so many companies entering the industry so quickly, some of the pioneers saw the sense of forming and being part of the British Ready-Mixed Concrete Association (BRMCA), which not only shaped the early technical standards for the industry, but also provided a valuable forum for the exchange of ideas. Trent Gravels played their part in this too, with chairman J. Stanleigh Turner and managing director Ken Potter elected as early BRMCA chairmen, while Roy Arthur, their production and technical manager since the 1940s, served on the technical committees.

At its formation in 1950 BRMCA boasted 21 members with 41 plants, but by 1963 the number of member companies had quadrupled to 82, with a total of 308 plants in operation.

In the early 1960s the British industry’s total output exceeded 10 million yd3 of ready-mixed concrete, a figure approximately equivalent to the output in the USA 30 years earlier. Today the country boasts some 1,500 depots and a production of ready-mixed concrete that has peaked at four times the 1960s figure and is currently around 30 million yd3 a year. Clearly, despite periodic downturns, the early prediction of a healthy future for the industry, by the editor of Cement, Lime and Gravel, has come true over the 70 years since it was made.

Bibliography

CASSELL, M.: ‘The Readymixers — the story of RMC’, Pencorp Books, 1986.

Directory of Quarries and Pits 1963–64, The Quarry Managers’ Journal Ltd.

Directory of Quarries, Pits and Quarry Equipment 2003–2004, QMJ Publishing Ltd.

HAY, D.C.: ‘Ready-mixed concrete haulage in non-agitating equipment’, Cement, Lime & Gravel, 1946.

JACKSON, G.P.: ‘The growth of the ready-mixed concrete industry in Great Britain’, Cement, Lime & Gravel, 1956.

KELMAN, B.N.: ‘Ready-mixed concrete and its significance for the aggregate industry’, Cement, Lime & Gravel, 1963.

WELLINGS, J.L.: ‘Ready-mixed concrete and central mixing plants’, Cement, Lime & Gravel, 1930.

WIGMORE, V.S.: ‘Ready-mixed concrete’, The Reinforced Concrete Review, 1961.